Westward Glances: Home and the Crisis of Language in the Work of Miriam Toews

A Truce That is Not Peace: Life and Death so Far by Miriam Toews

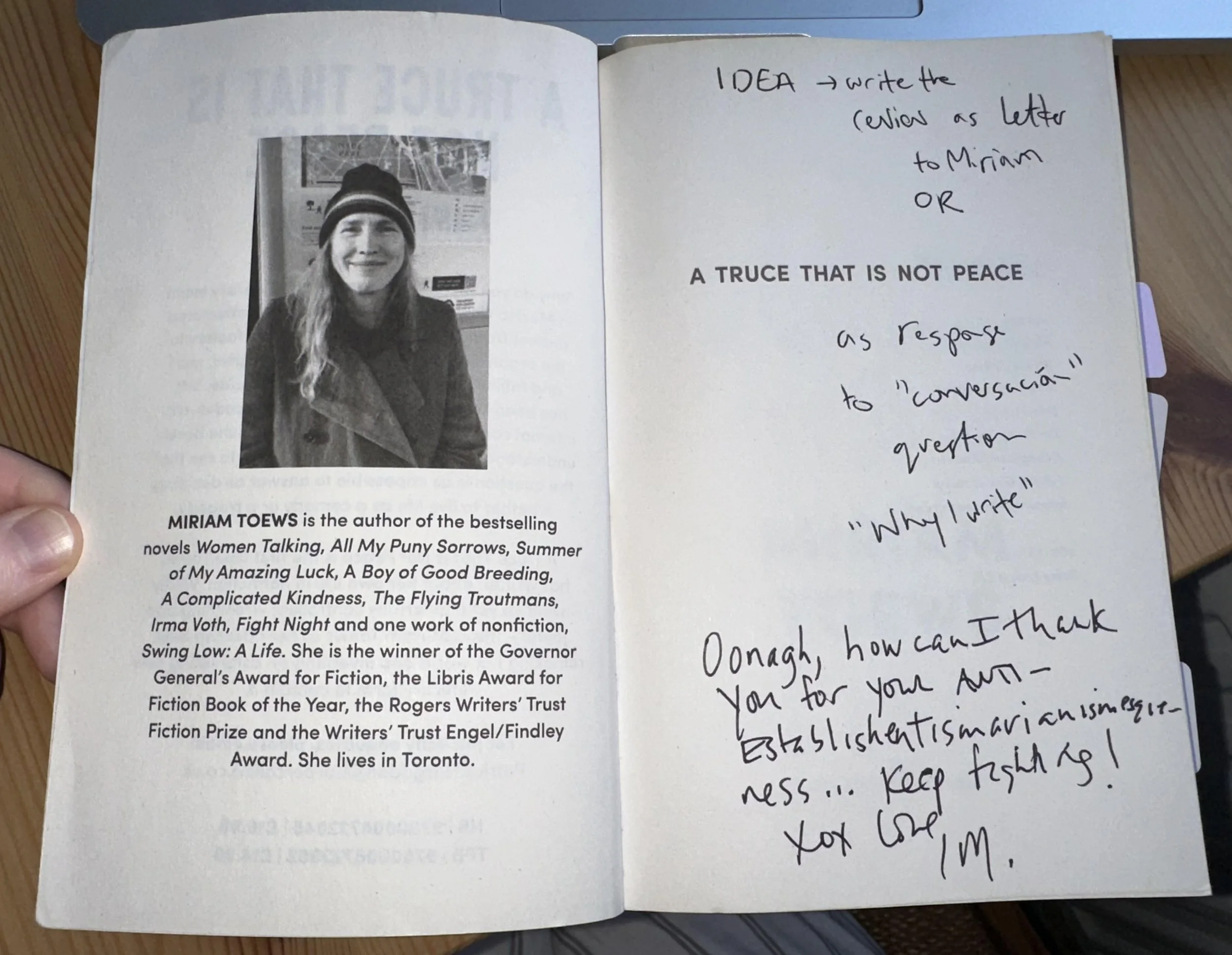

“Review” by Oonagh Devitt Tremblay

Sunday 6th July 2025

Dear Miriam,

I have a friend who works in a bookshop in Toronto, the city I grew up in but left several years ago. Because I know that you live in Toronto, and because I needed the answer to a question, and hoping for chance or kismet to have its way, in April I messaged this bookseller friend:

“If Miriam comes in the shop today please ask her which of her books has a sentence along the lines of ‘looking west as I would for my whole life’. Kidding but also not. Just paged through all my Miriams looking for a sentence I might have made up.” I did try to Google the sentence, but no combination of words resulted in success.

In May, I got a message from the bookseller: “Miriam came into the shop today. She did write it but who knows. She says hi. All my puny sorrows actually. She thinks.”

I was trying to find this sentence because it’s about being in a place where you have built your life and also, looking over and backwards at the place that built you: Homesickness as it were. Nostalgia, maybe. For you, a Manitoban living in Toronto this is west. For me, a Parisian raised in Toronto and living in London the broadest sweep is west, to the country that raised me, but also slightly southeast, to the city of my birth.

In your new book, A Truce That is Not Peace, you write about a recurring dream you have: “the one where I’m being shot in the face at close range and my mouth is flying off down some white corridor, and I’m so angry with myself for not getting out of the way in time”. Last night, as in the night before I started writing this letter, I had a dream that I couldn’t type. I was trying to send a text message and every letter that I typed came out as a different letter. Somehow the keyboard had been reorganised and I had no way to navigate it, or I did, but what came out was nonsense. Narratively, it is different from your recurring dream but ultimately, they are both about a crisis of language. Which is also, I think, what your new book is about. I’m not sure if it is a book really, or a thesis towards grief, or perhaps non-silence, or a meditation on speech, and the people in your life who learned to use the absence of it as its own language, one of violence, silence as a weapon etc. As you write in your new book, “I understand narrative as a failure. Failure is the story, but the story itself is also failure. On its own it will always fail to do the thing it sets out to do—which is to tell the truth. (Douchebag!).”

I am writing this letter to you, but it will (hopefully) be published, which means others will read it. A letter between two people is an experience similar to reading a book or writing a review as in, one which – despite feeling communal – happens in isolation. So, I see this response as an open dialogue in rejection of silence, experienced or to be experienced alone, paradoxically in silence. I see it as me saying hi back to you in the bookshop and being caught in the moment of waving. As such, I should perhaps clear some things up for those readers.

Miriam Toews was born in 1964 in Steinbach, Manitoba to a Mennonite family. She is the bestselling and award-winning author of ten books. A Truce That is Not Peace is her tenth. In 1998 her father took his own life and in 2010, her older sister did too. Both of them chose the same method. Both also chose silence for various periods throughout their lives. Miriam is a mother and grandmother and lives in Toronto in a multigenerational household. She said in a podcast episode (First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing), that she likes to write at her dining room table. Her new book is made up of letters, quotations, fragments, epistles and epigrams. In all of her books, you will encounter Mennonites and death and people across generations trying to get along and understand each other, and everyone has these insane names like Knute or Lish or Summer Feelin’ and the kids are so perfectly rendered and weirdly profound that they make you ache a bit. Actually, that goes for all her characters. Does that cover it? I’m asking this to all of my readers. I’m picturing them saying “no” and you saying why did you include that bit about the dining room table? To both, I say: “Let’s move it, move it, move it in a love direction”. This is something you write in your latest novel. This is something you said as a “traffic girl” when you worked for “the tiniest radio station in the province of Manitoba”, under the pseudonym of Lisa Cook.

That ache. Those children. The baby, torn from her mother in Irma Voth, who howls “for having no hair that she could twist around her little fist”. How can sentences hurt so much? I think it’s connected to the scale of the silence that your sentences are working against. “All silence is language” you write in Truce. Your books, especially this new one, interrogate and try to understand that language. Silence, like a baby’s howl, is very loud.

Once my bookseller friend wrote something to me that prompted me to ask her, “Have you ever been at a restaurant with someone who knows how to take all of the bones out of the fish in one go?”. The sentences you write have this same effect. Afterwards, I feel kind of like the fish skeleton – as in, stripped back to something essential, but also hollowed out. In Truce you quote from ‘The Glass Essay’ by Anne Carson, “The wind / was cleansing the bones.” Maybe what I’m arriving at is that some kind of bone cleansing wind blows through your books. Reading this book is a bit like crawling into the part of your brain that resists narrative, where thoughts come through unselfconsciously because formally you aren’t restricted by the devices of fiction.

Your book starts in April 2023: “I’ve agreed to join a “Conversación” in Mexico City. This is not really a conversation but an event where a series of writers from all over the world read a story or an essay or a thing they’ve written on a specific subject, a subject determined by the Conversación Comité in Mexico City. The subject this time is ‘Why do I write?’.” This is immediately followed by a Chekhov quote and a letter you wrote to your sister in 1995. This is how we proceed. Slingshotted between the past and present, the words of others, your words, your sister’s silence, your father’s too. The silence is there alongside your recurring dream, and your plans to make a Wind Museum and your life as a daughter/sister/mother/grandmother/ex-wife/partner/writer. “If silence says more, why write?” you ask in Truce. Maybe our answer lies in our hands, the hands that are holding your tenth book.

You write about carting Blue by Joni Mitchell (and other records) around Europe. You write about letters that your father and sister kept, your grandchildren who are going through a biting phase, bleeding in Blackwells, anger, sadness… You write about trying to answer the question for the Conversación and the committee refusing your attempts. I keep returning to the crisis of language. At your Sisyphean effort to overcome your father’s and sister’s rejection of language by answering the question raised by the Comité and then being silenced by them. I fear this is what will happen to me too, as I write this letter, which might be deemed unpublishable by the outlet who commissioned a Review of your Book. I want to tell you that the last essay I wrote during my undergrad was also deemed “unmarkable”. My professor said there was no way he could grade it but that I would pass the course. From a letter to your sister in 1982: “We agree that one set of things we need to experience is physical suffering, mental anguish, and total rejection from the establishment. I don’t really even know what the establishment is—but maybe that’s because I’ve already succeeded in being rejected from it. Like, from birth or whatever. So I can cross that off my list.”

While working on this piece, which has involved not just writing this letter but reading and rereading your Body of Work, I have listened: on purpose to Tanya Tucker’s Delta Dawn (readers who are not Miriam, see A Complicated Kindness), by accident to Joni singing California, and over and over again to Glenn Gould’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 73 “Emperor”: II. Adagio un poco mosso by Beethoven. "Adagio un poco mosso" is apparently Italian for slow, but with a bit of motion. This sounds like something Lisa Cook would have said in a traffic report. I have also listened on repeat to Hymns of the 49th Parallel by k.d. lang. This album is a compilation of original music and songs by lang’s favourite Canadian songwriters. The album title refers to the border between the United States and Canada and listening to it across an ocean from Canada makes you want to lie down and melt or absorb somehow into whatever surface will take you. This is kind of what your books do to me too. Like Anne Carson’s wind, like the fish skeleton. While k.d. sang Leonard Cohen in my flat, I returned to this section in Truce, where writing to your sister you describe a moment of fleeting happiness, “I just felt very calm for the first time in a long time, hearing this song. And normal. And happy and sort of excited about the future. It’s hard to describe. I felt like I was nothing.” And I think this is it, the nothingness and the normalcy of it all. That you can be listening to a song, which is also language and not silence, but feel whole in a transcendent moment of nothingness. Silence/language, absence/presence. Fort/Da. There, gone. What’s funny about this playlist is that Joni, Glenn and k.d. are all our neighbours. By which I mean Canadian. So is our friend Anne. It is not lost on me that the Joni song that has been coming into my life during this project is about her looking westwards. Lucy in Summer of My Amazing Luck says, “It’s true that life is not a joke. But I knew my life was funny”. What is also funny is that I found Glenn in The Flying Troutmans: “Let’s all be quiet. Let’s have a quiet contest. Okay, she said, but just so you know? Glenn Gould could do his playing, his live performances, while reminding himself of people to call”. I had forgotten I underlined this sentence but there it was waiting for me while Glenn played not so quietly (the one song) in the background.

Do you know who else crops up in your books? Northrop Frye. I live in England, and no one has heard of him. During my undergrad, I was in a foundational year program and my course was called, (I’m not kidding) the Northrop Frye Stream. In All My Puny Sorrows, your protagonist asks: “Is it even legal to disagree with Northrop Frye?”.

I did my undergrad in Toronto and mostly studied what you and me (Canadians) call CanLit. Like your characters, I bundled up and walked through Canadian winters. In A Boy of Good Breeding you write, “The world is full of possibility at that precise moment when winter jackets are taken off for the first time in Manitoba.” Most of those winters were spent waiting for that moment, trying to survive, trying to understand and by turns avoid life. I was also trying to answer the question that all the CanLit professors put in front of us students: “Where is Here?”

“It seems to me that Canadian sensibility has been profoundly disturbed, not so much by our famous problem of identity, important as that is, as by a series of paradoxes in what confronts that identity. It is less perplexed by the question "Who am I?" than by some such riddle as "Where is here?”

– Northrop Frye, The Bush Garden: Essays on the Canadian Imagination

In my pitch for this piece, I wrote that another version of this question is Where is Home. I think my professor Nick Mount might have asked this question. My university notebooks live in a weird attic cupboard at my parents' house in the middle of nowhere France. If I dug, I could probably find the notebook where I wrote it. I think this question is one of the key interrogations in your writing. All of your writing, and especially this new book, explores your Mennonite roots, your childhood in Manitoba, your life as a writer in Toronto, looking westward. What I mean to say is that you and this book, like your father and sister, are concerned with language, which might also be a kind of shelter, a kind of home. Or at least a truce with it. “Was my sister’s silence an attempt to translate something?” you ask in Truce. You also write:

“My sister punctuated her life with long periods of silence. It was during these periods that she begged me to write her letters—about anything, my life, my days—and in that asking was an offering. She taught me how to stay alive. Silence and words: both are good, both are failures, both are efforts, and in that effort is where life lies…. And the fragments in between are the spaces where she and I meet.”

You talk a lot of failure in this new book. You also talk about your suicide attempt. Is an attempt a failure? This attempt involved throwing your cell phone into the Assiniboine River and “being coaxed away from the shore and brought to the Victoria Hospital” where you had to undergo an “Official Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation”. You include your own spin on the evaluation:

“Have you been unable to stop yourself from crying, or really let’s call it weeping, for no reason other than everything?”

“Do you recall being held in your mother’s arms, the sun shining through a patterned curtain…”

“In the past, recent or distant, have you experienced a great subversive pleasure in opening all your windows to a sweet, cool spring breeze while keeping your furnace on and pumping warm air into your residence?”

“Do you remember riding your gold bike with the sparkly banana seat and the super-high sissy bar and feeling so free?”

Sometimes I think that if I could smell the lip balm I kept in my pocket in grade two that I might be okay for a while, that it might reveal something to me that makes the —what is it you call it — “Bone-deep rage” — navigable. In Swing Low, your other memoir, you ask, “Do you remember that time of life in the autumn of one’s adolescence when a thousand hopes and dreams seemed to clash with the realities of the world?”. Swing Low too was a memoir reluctant to the genre of memoir, because you wrote it in the voice of your dad. But “Writing isn’t talking. Writing is also non-talking” you express that in Truce. Memoirs can be written by the dead.

I want to ask what it is that you do at your dining room table? You write in Women Talking, “We mustn’t play Hot Potato with our pain. Let’s absorb it ourselves, each of us says. Let’s inhale it, let’s digest it, let’s process it into fuel”. Does what happens at your dining room table have to do with inhaling, digesting, processing? I think it might. I think it might also have to do with the letters that your father and sister kept for you, from you. And also, his and her absences of speech, and presence. This book has some parts of these letters, but I can also see how, over the course of your nine previous books, that you have always been writing letters to your sister and father, and this makes me so sad. I don’t know if I could answer Where is Here or Home, but I think I can locate this sadness in Truce, in your body of work, in my strange life looking west, south, east, namely, everywhere but here. In Fight Night, Swiv says: “He looked sad and happy at the same time. That’s a popular adult look because adults are busy and have to do everything at once, even feel things”. Everything at once, even feeling. Even talking.

The title of your new book comes from Christian Wiman’s Ambition and Survival: Becoming a Poet “…we might remember the dead without being haunted by them, give to our lives a coherence that is not ‘closure,’ and learn to live with our memories, our families, and ourselves amid a truce that is not peace.” You talk about the boat that floated away from you and your family during your childhood, “we’re sinking. We’re writing … We’re trying to go home. We’re all trying to get home.”

“What was she holding on to?” you ask about your sister. You continue, “For dear life”.

This letter is definitely not a review of your book. But it is a true response to A Truce That is Not Peace. I’m reaching westwards, towards you and the space between us. The space that is silence. I hope I am writing into it. “I toasted to our future or to the improbability of the moment, or just to its passing, or to private memories, or simply to the broader theme of shelter” you wrote in All My Puny Sorrows. Maybe this letter is a toast. It’s definitely an attempt. It’s definitely language, speech, articulation. It is definitely a rejection of silence.

Like your boat, like childhood itself, this letter has floated away from me. Like grief, like your book, it too resists closure. Nomi at the end of A Complicated Kindness says, “Truthfully, this story ends with me sitting on the floor of my room wondering who I’ll become if I leave this town and remembering when I was little kid…” So how does this letter end? It ends at my kitchen table, which is also my desk. It’s the next day now and I’m overwhelmed by the extent to which I may have rejected the establishment within this piece. I am also overwhelmed by the feeling of failure; this letter is not a review. I see failure, like silence, as an absence, it is nothing in the face of success’s wholeness. So here I am, with your book in my hands and this letter, a non-review. Gripping hard to a rope that a boat pulled away from the dock long ago. Nothing is attached. But the book is here, the sentences are underlined. “The immense altering of silence, of writing. It is the same” (Truce). You have altered the silences in your life by writing, I have tried to respond to this cosmic alteration of lack by writing into it. It’s windy today in London. Truce ends, “We all pause for a moment silent, before it begins” —so here I pause. I’m watching the wind rustle the leaves on the tree outside my window. I’m waiting for it to reach me, and then hopefully, eventually you.

All My Westward Glances,

Oonagh